That question is investigated empirically every year or six months at the Netherlands Institute for Advanced Study (NIAS-KNAW), housed in the oldest, seventeenth-century part of Amsterdam, the same neighbourhood where, again on De Wallen, I lodged in my student days (1981-88).

All these years later, on 31 August 2020, I start a five-month fellowship. Not only that, I’m returning to a youth elements of which have meanwhile been relocated and thoroughly reinvented. That old café in the Damstraat? Gone. The Damstraat itself? Far more tourists than junkies, and it used to be the other way around. And me? Long ago graduated, no longer an active member of the ‘academic community’, which exists by acclamation. Now it’s as a writer, as ‘Guest of the Director’ no less, that I’m back at the places where I once attended lectures and gave lectures myself as an assistant. Lost youth, lost academic career – yet also the unbelievably attractive idea that everything can start afresh.

My old neighbourhood, the things that have disappeared, but above all: a new place. A neatly laid out office, with desk, computer and telephone, and a view of a courtyard garden. Next to me and across from me are neighbours sharing the corridor, people no more than ten paces away, mostly academics, all with doctorates, some of them professors at Dutch or foreign universities (Nigeria, Canada, Germany, Sweden). You come upon them in the corridor, at the toilets, some leave their doors open, and just like on a campsite, you issue a friendly greeting if someone looks up. No need to carry the toilet roll under your arm. The last time I went camping, incidentally, must have been in 1981. The proximity of so many people: you can speak to them, perhaps you really ought to speak to them, because the thin walls are no excuse.

Then there’s our shared fate. We have all briefly been excused to work on our projects: the sociologist, the marine biologist (!), the philosopher and the historian. Are there shared interests too? Yes, certainly, but the principle here is that interests rub up against each other. In prevailing university practice the disciplines are clearly delineated – social sciences here, humanities there – but in their content they have so many interfaces that those dividing lines come to seem artificial. The NIAS aims to investigate the possibilities of an ‘interdisciplinary conversation’, to use the formal term.

The biweekly seminars, in which scholar X or Y talks about their research, are intended to facilitate knowledge transfer and debate. It’s a pleasure to be attending lectures again, especially now that it’s not for study credits. All that free information. Continually being brought up to date by people who have spent ten years engrossed in their field of study.

But when it comes to ‘community building’, you can surely expect most from informality: the lunches in the shared lunchroom; the chance meeting in the hall; and then there’s the garden, which cries out for white wine and relaxed conversation.

The marine biologist and I share a great love of the Balearic Islands. The garden enables us to discover this. The Nigerian, who usually lives and works in Canada, immediately starts behaving like an old friend who happens to have been out of the picture for fifty years. Three cheers for chance meetings, three cheers for unplanned, un-Zoomed conversation!

That’s how it was cautiously starting to look, that first month in September 2020. I say cautiously, because Covid-distancing prevailed from the start. A strange plastic flap had been attached to the toilet doorhandle; you stuck your sleeved arm through it and you were in. Plastic gloves and disinfectant wipes lay next to the coffee machine. We drank wine at a suitable distance, but in that warm afternoon sun. It all seemed like a prelude to many more beautiful experiences, but that one garden afternoon was the first of them and also the last.

In mid-October NIAS shut down. We stayed in contact via Zoom, via Teams or other ‘content information platforms’, but from that moment on, happy coincidence had barely any part to play. The international ‘fellows’ were stuck in their small bedrooms, the cafés and restaurants of the city closed their doors, and everything that ought to have developed informally now became a task, a computer assignment.

Everyone knows what talks and congresses are all about: the time afterwards, the contacts made in the corridors, the three participants who unanimously decide to skive off for an hour or so. Communities are created from a standing start through informality, and that informality cannot easily be relocated to a computer, no matter how sharply focused the camera or how immaculate the microphone.

It so happens that my own research explores the ‘informal boundaries’ of ethnicity and colour. In recent years, we in the Netherlands have spoken on the subject in terms of ‘black’ and ‘white’, plus that awkward residual category ‘people of colour’ for all those mixed types that cannot easily be allocated a place.

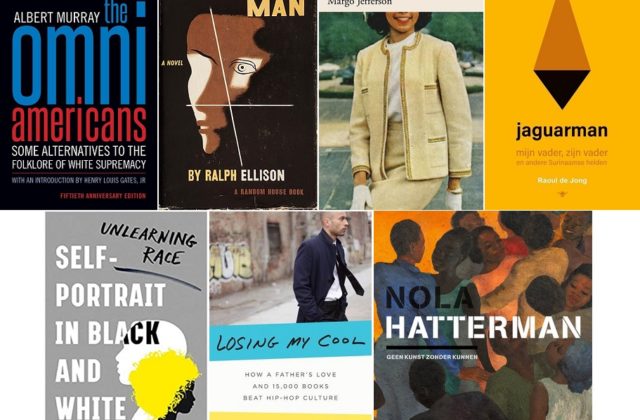

With the aid of various international authors (including Margo Jefferson, Thomas Chatterton Williams, Albert Murray, Ralph Ellison and Dutchman Raoul de Jong) I intend to show that the formal ‘black-white’ classification is unsatisfactory, both ethnographically and politically. Between black and white lies a whole spectrum of colours, from dark brown to light beige, and as far as I’m concerned it would be unthinkable to place all those people, against their will, within the formal, anti-racist framework, which is binary: black or white. There is an ethnic continuum, in which the formal boundaries do not apply. Colours and ethnicities bump up against each other, as in a children’s game.

At its best, NIAS is a luxury campsite, where people intermix, crossing the guy ropes. Friendly, interested, irritated perhaps. Which also means across the colour boundaries, because in practice those turn out not to mark any real boundaries at all but rather transition zones. The informal approach works best here by far.

The staff of NIAS did all they could, but Covid imposed strict limitations. What remained were the ‘formal appointments’: computer-driven, at a safe distance. There was no other option, but that great quote by doctor, philosopher and writer Bert Keizer remains valid: ‘The soul is in the body the way the mood is in the party…’

The soul of a community, a five-month camping community if it comes to that, relies on some unplanned carelessness. That too has been proven empirically during the 2020-21 term at NIAS.

Translation from Dutch by Liz Waters.