As a New Yorker, my first reaction to the excellent SPUI25 program featuring the NIAS Urban Citizen Fellows was one of jealously. Over the past several decades many cities, including my own, have taken steps to make urban governance more inclusive; to let citizens have their say—or at least to let them feel as if they do! Community input is generally accepted as a good thing and many cities are now exploring different ways to make it happen. But in few places would a municipal government invite busy-body academics to study these processes, much less to report on how they might go wrong. I cannot imagine New York politicians, planners and bureaucrats sitting still and politely listening as academics discuss the pitfalls and limitations of their efforts to democratize urban governance, much less supporting and partially paying for the enterprise! My long-held admiration for Amsterdam—both its municipal government and its social and cultural traditions— has grown even deeper.

Who is the community? Do the views of long-time residents take precedence over those of newcomers?

And yet, for all of the perhaps uniquely Dutch (or perhaps uniquely Amsterdam) good will and spirit of cooperation on display, many of the problems discussed are strikingly familiar to the foreign visitor. Giving “the community” its “say” obviously raises the question of who speaks for “the community”—indeed who is the community? Do the views of long-time residents take precedence over those of newcomers? I am not sure they should, but I am quite sure that many long time residents would disagree. When thinking about the future of a part of the city, how much should we privilege the voices of local residents – in effect the people who sleep there—over those of the people who work there, shop there or create and consume culture there? Do certain marginalized social groups – African Americans in the US, Jews in Europe, LBGT people almost everywhere – have a special relationship to those urban spaces in which they have historically found safety, autonomy and even a bit of freedom? Does this kind of cultural or, to borrow Sharon Zukin’s phrase, “moral ownership” extend to members of these groups who no longer live in these places? How do professionals and experts, even assuming all of the good will in the world, keep from imposing their definitions of the problems and limitations on the debate? And in today’s world, how do we create a “right to the city” for our fellow urban residents who live, work, raise their families among us yet lack legal authorization to even be physically present within the boundaries of the nation state, much less exercise the rights of citizens?

I also suspect that many of these professional “problem solvers” are uncomfortable with issues and problems that are clearly beyond their capacity to solve.

Anouk de Koning’s study of the dilemmas of “welfare state 2.0” throws many of these questions into sharp relief. With her keen anthropological eye, De Koning examines the results as well as the unintended consequences of efforts to create a more “intimate,” less fragmented and less alienating welfare system. Yet, even with the best of intentions, it is hard for the largely middle-class professionals running the system to avoid setting the agenda and defining the problems in terms they know how to address and, as a result, limiting the scope of discussion.

This is particularly clear when issues are raised around race. While generally committed to an ideology of “race blindness” these professionals risk imposing unconscious white middle-class standards. At the same time, they are reluctant to take up a specific discussion of race even when the clients understand issues in starkly racial terms. De Koning attributes this reluctance in part to the lack of training in how to talk about race, and this is undoubtedly correct. Yet I also suspect that many of these professional “problem solvers” are uncomfortable with issues and problems that are clearly beyond their capacity to solve.

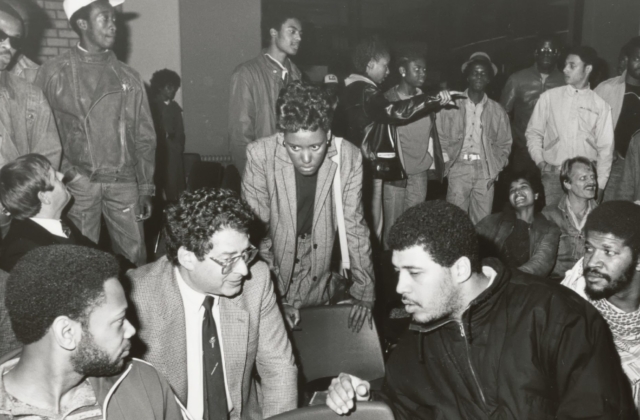

In Nanke Verloo’s account of the politics of citizen participation one can almost feel the frustration in the encounters between local activists and city officials and planners. Of course, most of the time relatively few citizens actually participate. Who can blame them? One is reminded of Oscar Wilde’s observation on the problem of socialism: it requires too many meetings. Thus, those who do participate are often self-appointed leaders whose voices are most likely to be heard simply because they care about a local issue more than most of their neighbours.

One is reminded of Oscar Wilde’s observation on the problem of socialism: it requires too many meetings.

These residents often enter this discussion already frustrated. For them, whatever local problem is at hand is just one more chapter in their relationship with the municipality. Today’s issue cannot be understood without being put in the context of a long history of grievance. Add to this well-earned and largely justified distrust that many working-class people have of middle-class professionals and experts, and you have a recipe for cynicism. And this, in turn, frustrates the professionals and planners, who can easily grow impatient with rehashing old battles. Often, they seek instead to define today’s problems in terms that are technical, limited and ultimately, solve-able; narrowly defined problems with limited but achievable solutions that often turn out to be less appreciated than they would like.

While Verloo’s study is critical, as an American I am once again filled with admiration both for the citizens, who are willing to put the time and effort into participating, and of the municipal officials who seem to actually want to encourage citizen participation, even if they are not always sure how to go about it. Yet it is hard for civil servants and technical experts not to set the boundaries of debate, even if that is not their intention. The result, Verloo reminds us, can be a de-politicized form of politics that leaves the would-be citizen participants once again feeling ignored, unheard and powerless.

Markha Valenta’s work, still in its early stages, puts front and centre an issue of vital importance in cities across the planet. How do we talk about “rights to the city,” indeed of rights at all, for the unauthorized, the undocumented, the illegal non-citizens who don’t actually have “rights” under most traditional liberal formulations? The idea of “human rights” is enshrined in the UN charter and other multinational organizations. Yet it seems clear that this notion has not been particularly successful in protecting the rights, welfare or even the lives of many people in today’s world. The right to migrate, to seek refuge and be granted shelter and safety, seems to be under attack everywhere.

This issue has been highly contentious in the US, the self-styled “nation of immigrants”. The movement of the “Dreamers” – young adults who came to the US illegally as children and are now seeking opportunities to fully participate in the economy and society of the only country they have ever really known, is a clear example. The Dreamer movement has taken up the tactics and vocabulary of the African American Civil Rights movement, the social movement that has been a model for so many other groups. Their marches, their speeches, the unselfconscious way they quote Martin Luther King, all speak to their cultural integration. So much about them seems so American! Yet while part of US society economically, socially, and culturally, the Dreamers remain excluded legally and politically. Thus, their lives are precarious and vulnerable. The Civil Rights model has limited utility for people who do not actually have many civil rights. As Valenta suggests, we need new ways of thinking about rights, solidarity and citizenship on our increasingly interconnected planet.

Urbanites, particularly urban youth, carve out identities more tied to the city than to the nation.

This brings us to a question of “urban rights” and the role cities can play in welcoming and protecting their denizens. Here European cities have generally been more proactive than American ones, for example, by granting voting rights in municipal elections and other forms of political participation to non-citizen residents. And on both sides of the Atlantic, urbanites, particularly urban youth, carve out identities more tied to the city than to the nation. The young adults of immigrant parentage I studied in New York often asserted that, while they did not feel strongly “American,” they did see themselves as “New Yorkers” – much as their counterparts see themselves as Amsterdammers (or Berliners or Londoners). And many of the children of natives seem to share this identity, at least in part. Whether these identities are rooted in urban practices and communities (as Lefebvre would suggest) or in the blasé tolerance emerging from the experience of everyday life in the metropolis (as Simmel would have it) or in the simple fact that cities tend to attract those with a taste for diversity and repel those without it, it does seem that different notions of societal membership emerge on the streets of diverse cities.

How can we give these notions a political form? In my country efforts by municipalities to grant rights to newcomers are now routinely undercut by state governments which have the power to limit municipal innovations. And even in the tolerant Netherlands, Amsterdam’s autonomy is limited by a national government that includes parties who, as Deputy Mayor Groot Wassink articulately put it, “think we are cuckoo”.

Indeed, the unpredictable and serendipitous encounter, so much a defining feature of urban life, has been among the first casualties of the pandemic.

Clearly, these presentations have left me with more questions than answers. Thus, in lieu of a real conclusion, I will raise one question more. What does Covid-19, and, more specifically, the withdrawal from public space it has necessitated, mean for “rights to the city”? Today most of us are socially distancing among people – our relatives and nearest neighbours – who are often very much like ourselves. We have withdrawn from the very places where we used to engage with “the other” and encounter difference. Indeed, the unpredictable and serendipitous encounter, so much a defining feature of urban life, has been among the first casualties of the pandemic. How and when will we return to these spaces? And will we find we prefer to live without them? It is too early to say. Yet as these excellent presentations show, the next few years will offer new challenges to our efforts create a more humane, more just and ultimately more democratic city.