The present text consists of two parts: in the first part information is given about the current situation of NIAS in Amsterdam and about our ambitions, whereas the second part is focused on imagination, the mysterious driving force behind science and art.

There is in this world something that is more valuable than material pleasures, or wealth or even health and this is the dedication to science.

Ernest Renan (borrowed from Henk Wesseling)

I. NIAS

NIAS is an independent interdisciplinary Institute for Advanced Study that fulfills a unique role in the academic landscape of the Netherlands. The facilities at NIAS encourage researchers from disciplines who would rarely mingle in daily university life to meet and interact, to produce new alliances and find scientific directions aimed at new research-questions or at solving relevant societal problems. Collaborations between humanities, social sciences and natural sciences are actively supported at NIAS.

NIAS is an international, interdisciplinary community where scholars can work independently and in freedom, undisturbed by daily obligations and driven by curiosity.

The current research climate, of applying for subsidies and grants from the national funding organisation NWO or Brussels, prioritizes large-scale projects involving several institutes and PhD students. In contrast, NIAS offers independent and individual grants in the form of fellowships (3, 5, or 10 months) that allow scientists to work on a smaller-scale within interdisciplinary partnerships to trigger new ideas and/or to complete publications. There is no other institute in the Netherlands that offers scholars such opportunities.

NIAS was set up in 1970 and, apart from Princeton and Stanford, it is one of the longest established institutes of advanced study in the world. NIAS was the first institute of advanced study in Europe and it has an outstanding international reputation. It takes an active part in two international networks: SIAS – the prestigious transatlantic network of nine institutes of advanced study (Princeton-IAS, Radcliffe-Harvard, CASBS-Stanford, NHC-North Carolina, IIAS-Jerusalem, SCAS-Uppsala, NIAS-Nantes and WIKO-Berlin) and since 2007 NIAS has been also a member of NetIAS, the European network of 21 institutes of advanced study from 19 different countries.

During the years NIAS succeeded in improving its quality. Many distinguished individual scholars were fellows. At this moment the NIAS belongs to the best institutes for advanced study in the world and it is our ambition to continue this front-row position. The number of academic disciplines significantly increased during the years. Two decades ago fellows were primarily from the domain of the humanities with a majority of historians and literary scholars, but now in 2017 about 19 academic disciplines are present from 16 countries and through our relationship with the Lorentz Center in Leiden an intellectual bridge has been built between the social sciences, the humanities and the natural sciences.

The Divide

Crossing disciplinary borders will be further stimulated. In fact, the sharp demarcation between the scholarly domains took place at the end of the nineteenth century. In a famous lecture held by the German philosopher Wilhelm Windelband in 1894 in Berlin he distinguished between the natural sciences that are nomothetic and the historical and cultural sciences that are idiographic. He argued that the sciences are on earth to explain (Erklären), whereas the humanities are there to understand (Verstehen). The distinction between Erklären vs Verstehen was born. “Die Geschichte einer unglücklichen Gegenüberstellung” as it was termed in a recent German PhD thesis, and digital humanities scholar Rens Bod is right when he indicated in De Vergeten Wetenschappen that this sharp separation did not exist in earlier ages and often is artificial.

The use of the word science in the narrowed sense, solely referring to the physical or natural sciences appeared in English only in the middle of the 19th century. Before 1860 the Oxford English Dictionary gives no example of this distinction. The first course in the natural sciences at Cambridge was in 1850. But there was serious resistance because the natural sciences were not seen as suitable for the proper education of a gentleman. The sciences were seen as an inferior activity. In 1882 Mathew Arnold argued that training in the natural sciences might produce a valuable applied specialist, but not an educated and civilized man. For this, the classical literature remained indispensable.

In his famous 1958 Rede Lecture the British chemist and novelist C.P. Snow sharply criticized this attitude that remained to play a role throughout the first half of the 20th century. The criticism was strongly influenced by his opinion about science. He saw science as the great hope in a world which the traditional elites had mismanaged and led into economic depression and two devastating wars within a period of thirty years. He also saw science as a true meritocracy in which sheer ability and talent could overcome social disadvantages. Snow criticized the gap between the cultures, but he attacked in particular the arrogant and elite attitude of the literary intellectuals and the humanist scholars. He was absolutely convinced of the greater moral health of scientists as a group over literary intellectuals. Scientists, and I cite Snow “are by nature more concerned about the collective welfare and future of humanity” and he presents an extraordinarily tendentious selection of examples such as the political decadence of Ezra Pound finishing broadcasting for the fascists and Faulkner giving sentimental reasons for treating Negroes as a different species. He accused the literary culture of hostility to the scientific revolution. He describes the following scene:

“I think it must have been at St. Johns or possibly Trinity. Anyway Smith was sitting at the right hand of the president and he was a man who wanted to include all round him in the conversation although he was not encouraged by the expressions of his neighbors. He addressed some cheerful Oxonian chit-chat at the one opposite to him, and got a grunt, He then tried the man on his own right hand and got another grunt. Then to his surprise one looked at the other and said “do you know what he’s talking about?” “I haven’t the slightest idea”. At this moment even Smith was getting out of his depth. But the president acting as a social emollient put him at ease by saying “Oh those are mathematicians, we never talk to them”.

The declared separation between two large domains of human knowledge resulted in the perception of two cultures divided by an intellectual wall. A separation reinforced by stereotypes. Literary intellectuals at one pole, at the other the physical scientists – between them a total lack of understanding. They have a curiously distorted image of each other. The divide was a fact.

According to C.P. Snow the breakdown of communication between the “two cultures” of modern society — the sciences and the humanities — forms a major hindrance for solving the world’s problems.

The Beginning

In 1932 Abraham Flexner had a dream. In a world full of political threats he wanted to found an “institute devoted to unrestricted research at the frontiers of knowledge”. This institute should create an infrastructure of opportunities for the greatest minds in the world. The philanthropists Louis Bamberger and his sister Caroline were so impressed that they decided to donate five million dollars. And in November 1932 the Princeton Institute for Advanced Study was a fact.

Princeton was the first IAS in the world. It was established in a world where freedom of thought and the independence of science were under extreme pressure. This was particularly the case in Germany where Adolf Hitler was on the edge of taking over power and his poisonous anti-Semitism formed a direct threat to many scientists. But also other countries showed a rapid worsening of freedom of thought. The events in Germany and other parts of Europe in the 1930ths and 1940ths led to a definite change in the intellectual landscape of the world until now.

The Princeton IAS provided an institutional hope for many famous intellectual refugees and the institute adopted many European top-scientists at risk. The fact that Albert Einstein became the first director is a clear example of this.

It was Flexner’s lifelong belief that human curiosity with the help of serendipity was the only force strong enough to break the psychological barriers that block truly transformative ideas and technologies, the only force that is strong enough that it may lead to disruptive innovation.

Of course the path from blue sky research to practical applications is not one-directional and linear, but rather complex, chaotic and cyclic, but history of science learned that it is the only way that on the long run leads to progress.

The Netherlands

In 1959 the idea was born, particularly in Leiden, to found such an Institute for Advanced Study, also in the Netherlands. In the beginning the thoughts went in the direction of a European institute for all scientific disciplines, but during the slow process of establishing the institute this ambition was abandoned.

It remained politically silent until 1970. In that year the process accelerated since in Wassenaar buildings became available that fit well with the objectives. The ministry of Science and Education decided to make the money available necessary for purchasing the buildings at the Meijboomlaan. In 1970 the Netherlands Institute for the Advanced Study of Humanities and Social Sciences (NIAS) was established. In addition to Princeton and Stanford, it was the third IAS in the world and the first one in Europe. It was modelled on the Stanford Center.

Why is NIAS still important and needed?

Some – I call them utilitarians – consider an Institute for Advanced Study as an unnecessary luxury in a fast and competitive world. But if we look closer at the core mission of an Institute for Advanced Study, namely the enhancement of science in an interdisciplinary and international context, this becomes a remarkable opinion. The enhancement of science by focusing on independent research driven by curiosity seen as a luxury, is actually attacking the essence of science and proves how far we have driven away from what science is about.

The wish to “capture” the results of research for economic purposes has substantially increased during the last years (in the Netherlands this policy was termed “topsectorenbeleid”). In spite of all counterarguments this “utility” concept of science reduced the scope and the resources for free academic research at the universities. The humanities and the arts clearly suffered from this neo-liberal approach. Universities run the risk that they become organized to serve the interests of the economy instead of defending the value of knowing.

Let us not forget that throughout the history of science most of the really great discoveries which ultimately proved to be beneficial to mankind have been made by man and women who were not driven by the desire to be useful but merely by the desire to satisfy their curiosity.

And like in the thirties of the last century, the world is still not a safe place where democracy and free societies dominate. Also now dangerous nationalist sentiments and emotional views on history and national identity are blurring man’s rational abilities. It seems that history may play a guiding role only in individual lives but not in that of collectives such as societies. Dangerous trends are visible, guided by psychological processes similar (not identical) to the ones that played such a poisonous role in the first decades of the twentieth century. The so-called new right has become a powerful counterculture. With white ideals of isolationism, protectionism, nationalism and a closed nation-state. This has to be taken seriously.

Donald Trump is now president of the United States, having won on a campaign that trashed liberal democracy itself, and is now presiding over an administration staffed with defenders of a political philosophy largely alien to American politics until now. In Russia, Vladimir Putin has driven his country from post-communist capitalism to a new and popular czardom, empowered by nationalism and blessed by a conservative Orthodox Church. Britain, where the idea of free trade was born, is withdrawing from the largest free market on the planet because of fears that national identity and sovereignty are under threat. In the Netherlands, the anti-immigrant right became the second-most-popular vote-getter — a new high-water mark for illiberalism in a country that once was famous for its liberal atmosphere. Austria narrowly avoided installing a reactionary president in last year’s two elections. Japan is led by a government attempting to rehabilitate its imperial, nationalist past. Poland is now run by an illiberal Catholic government that is dismembering key liberal institutions. Turkey has morphed from a resolutely secular state to one run by an Islamic strongman, whose powers were just ominously increased by a referendum. Israel has shifted from secular socialism to a raw ethno-nationalism. We are living in an era of populism and demagoguery.

And in this world also curiosity-driven scientific research is under pressure, and again efforts are being made to clamp down the freedom of the human spirit and scientist are at risk and need safe havens.

This makes NIAS also in 2017 important and needed. An institute characterized by a limited number of duties and many opportunities, a place where imagination can fly, research is free and curiosity still counts.

Arts and Sciences

At NIAS a jumelage took place between the arts and the sciences, a relationship which I see as extremely important. Indeed, arts and sciences are connected to each other through the mysterious process of imagination that drives science as well as the arts. But there are also differences between the arts and the sciences. I argue that science is characterized by progress while art in itself is not directed at progress. Art is changing across times, the employed materials may differ as well as the selected themes, art can be innovative, but art is not intrinsically driven by the continuous expansion of knowledge leading to progress. Art is not a cumulative knowledge process. Scientific knowledge can be obsolete, but in art you seldom hear somebody saying how glad we are that we not have to suffer from the old fashioned attempts of Rembrandt, Leonardo da Vinci and Bach. Art in a way is eternal, science is not.

II. IMAGINATION

Imagination is one of the most mysterious and fascinating faculties of the human mind. It was long a forbidden fruit on the menu of psychology, but since the beginning of the cognitive revolution it attracted attention again. To be honest we do not know what imagination is. We can describe it in phenomenological terms, we can experience it, but we do not know how it is organized and how it is controlled by the brain. As a concept imagination has much in common with consciousness. Imagination enables us to reflect on our behavior and to project our behavior to a future situation. Imagination, in fact is the laboratory in the head where actions are tested off-line before we execute them.

Imagination is the ability to construct images in the brain that are further concretized and visualized to generate ideas and behavioral prototypes that may solve problems in reality. In a way imagination is the laboratory in our head where actions are tested off-line before we execute them.

It is not clear whether humans are the only animals that possess this skill, since fragments of it have been found in monkeys, dolphins, elephants and crows. However, in this lecture I focus on humans who use this mental power for science and art and for unraveling the secrets of life and the planet.

Humans are most free when they are engaging in imagination. Perception shows only the actual, but imagination can go beyond that, to the realm of the maybe. When human beings encounter the unknown, imagination becomes the guide. Imagination is an innate ability of human beings, it is the basis for all creative activities and the result of cognitive and emotional processes. Imagination constantly affects our language, our thinking and experiences. Imagination is not hindered by rules, nor is it hindered by current modes of thinking.

For an 18th century empiricist imagination explains how we can think when there are no impressions presented to us. Hume, for example considers imagination as a sort of pseudo-memory.

During the enlightenment imagination had a Janus face, on the one hand it was essential for creativity but on the other hand it could betray the natural by breeding monsters. Enlightenment savants distrust the imagination, since how to construct a world not reflected in sensation but made up by imagination? They feared the corrupting effects of imagination because they saw a real danger in losing oneself in illusory images and thoughts. Imagination had a fearsome power to conjure misleading worlds that could drive a person mad. Clarity and correctness of facts became the goals.

The great French naturalist George Cuvier made a distinction between true discoveries and romances. He put the faculty of reason opposite the faculty of imagination.

There are many places where imagination cannot fly, but NIAS is a place where imagination is cherished. Scientists and creative artists have (or should have) the amazing gift of being able to think out of the box and allowing their imagination the freedom to grow. To create ideas and products that change the way we think and live. Simply put imagination is the key ingredient to the advancement of our world. Thoughts may become things.

We are able to imagine almost everything. Standing here in the Conference Room at NIAS, I can easily imagine that I walk outside the city on a country road. I can imagine scenes or objects that are not there, or no longer there. I can mentally perform actions which I cannot perform in reality. I can imagine myself as a perfect dancer although reality has learned that my motor networks are very reluctant to learn the repetitive and rhythmic motor patterns needed for that type of skill. I can move myself to my house in France, I see the hills and smell the odor of the fireplace. I am a wizard, but the point is we are all wizards, we are all equipped with this ability, and without this skill science and art would not be possible. This imaginative power can be used in the visual, auditory, and tactile domains and in the domain of science and art. Imagination is needed to write a poem, paint a picture, compose a piece of music, design an experiment, write a book, make a movie or invent a new product. The scientist like the artist feeds his imagination with surprise, wonder and curiosity.

The Dutch author Gerrit Komrij writes: “The writer can dignify a beggar, dethrone an emperor. He can create popes, butchers, cable joggers, widows, princes, nurses and dairy farmers. And he can kill them all, if he wants” (Verwoest Arcadië, p. 31).

Although we seem to be able to imagine everything we want, it is at the same time extremely difficult to imagine something totally new. In a famous study, Ward (1994) asked participants to draw a front and a side view of a creature from a planet somewhere in the universe. The drawings exhibited some very informative regularities. For example, people tended to make sure that their alien creature had sensory and motor organs, most commonly eyes and some form of legs. These regularities suggest that when people imagine totally unknown organisms they do this by modifying a concept that they already know. Inventions of something new are structured (most of the time) by existing knowledge. When the instruction was to draw something with feathers they draw also wings, which was not the case when the instruction was to draw a creature with fur.

In a follow-up study (Ward et al. 2002) subjects were asked to imagine tools that might be used by a highly intelligent species of extraterrestrials with the following constraints: the tools are not to be operated by power sources and the creatures do not have arms, legs or other appendages. Despite these constraints most drawings showed common tools such as hammers, saws and wrenches that were modified so that they could be wrapped around their heads or to hold them in their mouths. This tendency to rely on existing knowledge to guide creativity is termed structured imagination.

Also religious imaginations do not exhibit an unlimited cultural variation but are constrained by prior ontological expectations, there are no gods that exist only on Wednesday and all gods have intentions, desires and emotions. They conform to a normal common sense psychology.

Given that scientists are subject to the same cognitive limitations it can be argued that scientific creativity is likewise structured and constrained by prior knowledge and expectations. The historian of technology Basalla (1988) amply demonstrated that newly invented devices are nearly always based on already existing artifacts. Many studies showed that scientific imagination and creativity draws on the same cognitive resources as everyday creativity. As a consequence scientific creativity and imagination mostly works with small incremental steps, rather than revolutionary leaps.

Nevertheless sometimes paradigmatic shifts take place such as with Darwin and Wallace who moved away from individual essentialist thinking to population thinking. But again the shift came not totally out of the blue but was influenced by Malthus’ essay On the principle of population that was published in 1798. Prior to Malthus biologists did not notice populations but focused on the essential characteristics of individuals.

Imagination is a treacherous friend

Imagination is a powerful mechanism but it is for a large part not controllable by will. Sometimes it is river of inspiration, a flow of thoughts, almost unstoppable. At other times the river has dried up, no flow at all, only waiting time and frustration. Imagination works often behind the curtains of consciousness. The poet T.S. Eliot wrote “I only know what I want to say, after I said it”. The German critic Lichtenberg was even more clear with his expression “Es denkt in mir”. The Dutch author of short animal stories Toon Tellegen wrote “I am going to think about something totally new, I am curious what that will be”.

In spite of the mysterious character of imagination, we are never without. It is almost impossible to switch the mental screen on black without any thoughts or impressions. We cannot imagine how mental life would look and feel without imaginations. I would be lifeless, cold and empty.

The composition of a novel is the result of the writers’ imagination, but at the same time it is transferred to the imagination of the reader. Reading can result in visual or auditory images, generated in the brain of the reader. An almost immediate transformation has to take place from text to sensory experiences and fMRI studies show that this is what actually happens. Reading a text picturing a world of colors activates brain areas responsible for perception of colors, while a text that describes movement results in the activation of the motor areas.

It is if Flaubert and Rilke were aware of this, given the excess of color and movement images in their writings.

Imagination and Imagery

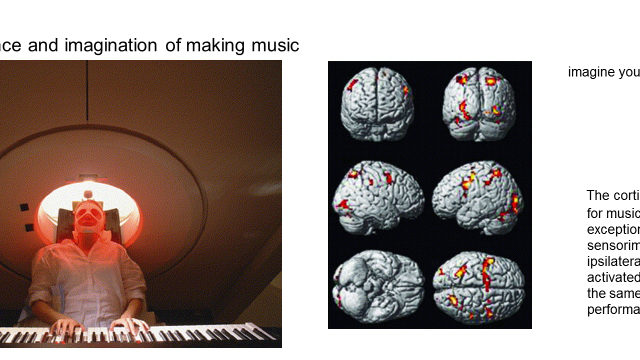

Imagination as a cognitive ability is based on the act of imagery which means the formation of mental images, events, movements, ideas that can be seen, felt and experienced but are not present in reality. We are able to mentally imagine the performance of movements together with all the sensory consequences.

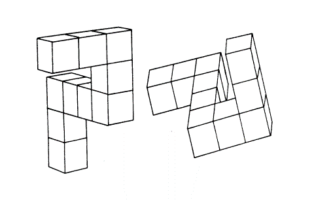

Let me give you a simple perceptual example. If I ask you whether the two figures are the same, it takes you about half a second to make a decision. This is not at all trivial, since the figures are not present in 3-dimensional space and in order to be able to decide that the figures are identical, you have to rotate them for your mental eye. You are able to do this without problems. Is this perception? Not really. Although we seem to see the objects, it is a quasi-observation. If I ask you to describe your house or to rotate the above-mentioned figures you are capable of doing that, but if I ask you to imagine a zebra and count its stripes you cannot, it is simply impossible. So imagination is not a mode of perception. There is no such thing as the mental eye. Dennet speaks about the illusion of the Cartesian Theater.

Let me give you a simple perceptual example. If I ask you whether the two figures are the same, it takes you about half a second to make a decision. This is not at all trivial, since the figures are not present in 3-dimensional space and in order to be able to decide that the figures are identical, you have to rotate them for your mental eye. You are able to do this without problems. Is this perception? Not really. Although we seem to see the objects, it is a quasi-observation. If I ask you to describe your house or to rotate the above-mentioned figures you are capable of doing that, but if I ask you to imagine a zebra and count its stripes you cannot, it is simply impossible. So imagination is not a mode of perception. There is no such thing as the mental eye. Dennet speaks about the illusion of the Cartesian Theater.

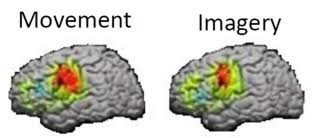

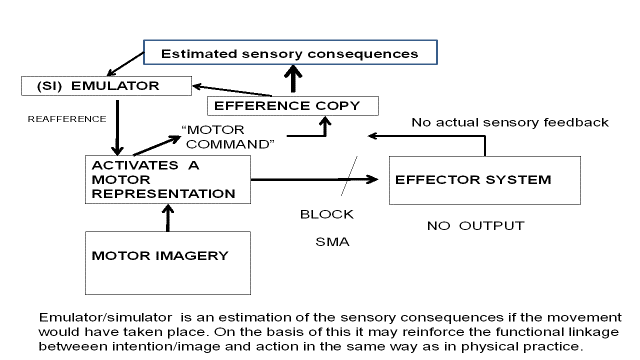

This brings us to the fascinating point that imaged events for the brain are to a large extent real events. If you imagine a certain action, say walking or grasping without actually performing the act, the same brain areas become active as when you would have actually performed the movements.

And if I ask you to imagine that you walk to that door and to let us know when you are there, the time difference between the actual action and the imagined action is negligible (but not when I ask you to imagine that you carry a heavy object or if I ask you to imagine that you walk backward).

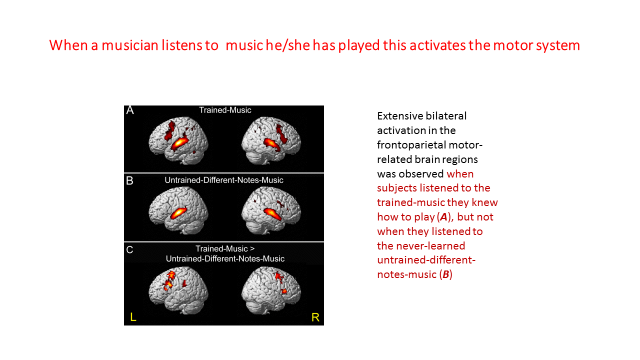

And this is not only true for trivial acts such as simple movements but also for complex actions such as making music and listening to music. When a trained musician listens to music he is familiar to, his sensori-motor areas in the brain become active, as if he is actually playing the music.

And it becomes even a bit weird when we realize that actions normally are learned by physically exercising them, but also and to the same extent by means of repeated imagery of that action.

Strange isn’t it? How is this possible?

Local cortical connections and responses are continuously reorganized as a result of peripheral and central alterations of input. In other words, experience can modify brain structure. This ability of sensory and motor cortices to dynamically reorganize is an important component of normal learning and recovery after neural injury. The point is that self-generated input, as is the case in imagination functions in the same way. Imagination plays a role in modifying the brain, it functions in a similar way as activity-dependent information.

Against this background it becomes clear why imagination can be employed for controlling machines. The generated internal feedback can be measured as an EEG signal and this signal can be used as an input mode for a robot or other machines, for example a mentally driven wheelchair as developed by Wolpaw.

Observation and imitation

Imagination is closely related to observation and imitation and it seems plausible to argue that this triage OBSERVATION – IMITATION – IMAGINATION forms the foundation of fantasy and creativity.

A renewed interest in observation and imitation took place after in Parma the so-called mirror neurons were discovered. This discovery is a clear proof of serendipity since the research team was not at all looking for this type of neurons, they were studying the neural control of reaching in the monkey. However, in a pause they observed that motor neurons fired not only when the monkey performed a reaching movement toward a peanut but also when the monkey was looking at a person who was picking up a peanut. It was difficult to believe that motor neurons were sensitive also to perceptual information.

But that was what these neurons did, they reacted to motor as well as to perceptual inputs and by this formed an important source for lifelong learning. Indeed, observing an act resulted in a motor resonance, observing an act leads to the tendency to perform that act.

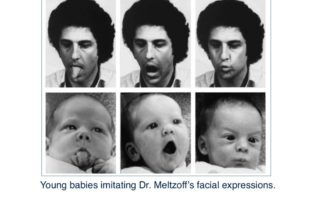

By means of observation and imitation we are able to understand the nature of actions performed by other humans. Observation became a much more interesting phenomenon than often thought and that is also true for imitation. Indeed, during observation and imitation perceptual information has to be transformed into motor commands related to the observed movement. That this has not to be learned is shown by the famous experiments of Meltzof that indicated that even newborns (48 hrs old) imitated facial expressions.

By means of observation and imitation we are able to understand the nature of actions performed by other humans. Observation became a much more interesting phenomenon than often thought and that is also true for imitation. Indeed, during observation and imitation perceptual information has to be transformed into motor commands related to the observed movement. That this has not to be learned is shown by the famous experiments of Meltzof that indicated that even newborns (48 hrs old) imitated facial expressions.

During observation around twenty percent of the motor neurons responsible for executing the action become active. This forms a strong innate mechanism for learning, it has not to be learned and it functions without any instruction.

Mirror neurons form an important discovery, but let us be honest. It is still a question whether they exist in humans in the same form and with the same function as in monkeys. It is, indeed, not possible to measure these neurons directly in humans. Hence, the neurons play an important multi-sensory role in sensory motor control, but they do not explain all aspects of language, emotion, empathy and world peace.

Why are humans able to imagine unknown worlds?

We are born with the ability to imagine. It is an important evolutionary “gift”, not primarily intended to write novels and poems or to make paintings or perform science. So it must have a clear survival value. This brings me back to my earlier remark, that imagination forms the laboratory in the head, which means that not everything needs to be actually performed in order to be accepted or rejected. If we could not assess and test our actions off-line in our head life would become more risky than it already is. If imagination would not exist, we would be dependent on the feedback and the consequences of behavior, actually performed, which could be life-threatening. Imagination is needed to assess consciously and unconsciously the consequences of our actions.

This assessment takes place continuously in everyday life, without being aware of it. When my hand reaches the knob of a door, it is exactly on time in the correct position. This can be done only when we have knowledge about the form and function of the object and link that knowledge to the current action. Some argue that the visual information of the knob elicits the correct action “directly”, but this does not mean that this takes place totally independent of knowledge. We pick up a sharp knife different from a pencil. Imagination accompanies our behavior as a shadow. Imagination functions in permanent interaction with memory, it is almost never totally new but always influence by stored knowledge. Memory disorders result also in disorders of imagination.

Imagination can be seen as the creation of a future memory. It is the relation between actual thoughts and former memories that forms the foundation of something new.

References

Basalla, G. (1988). The Evolution of Technology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Ward, T.B. (1994). Structured imagination: the role of category structure in exemplar generation. Cognitive Psychology, 27, 1-40

Ward, T.B., Patterson, M.J., Sifonis, C.M., Dodds, R.A., & Saunders, K.N. (2002). The role of graded category structure in imaginative thought. Memory and Cognition, 30, 199-216.