Knowledge and the City, ca. 1450 – ca. 1800

Year Group 2015/16

About the topic

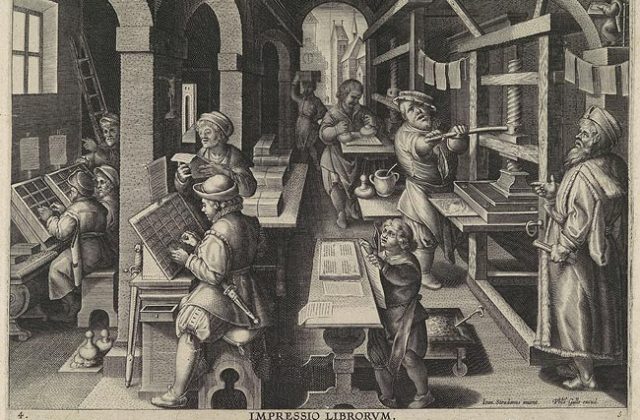

It is generally accepted that knowledge production is to a large degree an urban phenomenon. While a range of sociologists and economics propound that cities accommodate the creative classes and that urban spaces are conducive to innovation, the origin of the modern knowledge society would have to be sought for in large, early modern cities such as Antwerp, Amsterdam, Paris and, in particular, London.

However, neither a city nor knowledge can be reified or be seen as ‘bounded’ entities. Urban historians currently refrain from reducing cities to a political body or community (as in a communitarian political perspective) or to the ‘absence of distance’ (as economist would be tempted to do). Nor can a city be reduced to either a set of institutions or a spatial and material reality. Under the strong influence of Science and Technology Studies and Actor Network Theory, cities are now seen as ‘assemblages’ of human and non-humans ‘actants’ including material objects, matter and techniques; human bodies, thought and feelings; institutions, discourses and practices; and – last but not least – knowledge.

Simultaneously, and to a large extent under the influence of similar theories and concepts, knowledge has been de-naturalized and unpacked. Rather than resulting from the cerebral thinking of a limited set of intellectuals, knowledge is now considered to emerge from networks involving such different actors as instrument makers, surgeons, mathematicians, engineers, alchemists up to and including merchants, gardeners, and collectors. The networks in which these people operated were multifaceted and asymmetric and they materialized on different scales – from very local and place-bound to global. Moreover, they involved different types of practices, which in turn were predicated on different types of instruments and other immutable mobiles involved.

Last but not least, knowledge and the city are mutually implicated. Firstly, the city as an assemblage and the contexts, networks, institutions and infrastructures from which knowledge emerges partly overlap. In addition, knowledge and the city are intimately entangled owing to their mutual need for justification. The alleged superiority of certain forms of knowledge is often legitimized with reference to the context in which it is formed and used. This context can range from a certain institution (a university, an academy, a guild etc) up to the European or Western context as a whole, but the city as well is relevant here. After all, urban actors themselves will often refer to the city as a superior context when it comes to the justification of innovation and knowledge formation.

In all, the city and knowledge often co-emerge and are co-produced in a range of hybrid networks involving a range of complex and entangled practices. Our project sets out to examine this co-production and these practices through a range of case-studies and via different conceptual approaches. We concentrate on the early modern Low Countries, in the full knowledge that the concerned cities were, of course, implicated in networks stretching far beyond this region.

by Bert De Munck (theme group coordinator)

Descartes Theme Group

This Theme Group is part of a long term collaboration between NIAS, the Descartes Centre for the History and Philosophy of the Sciences and the Humanities (Utrecht University), the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science (Berlin) and the Huygens ING (The Hague). Read more about the global knowledge society project or read more about Descartes theme-group fellowships…

Michael Tworek (Harvard University) was a Theme Group Guest.