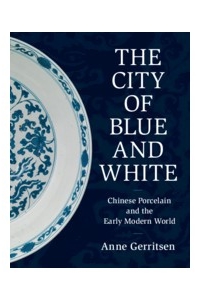

Anne Gerritsen on China’s porcelain shard market

Research Notes | The Fragmented History of China’s Global Past

25 June 2014At first glance, a local market devoted only to the sale of broken pieces of ceramics might seem an odd place to begin a research project. How can dirty old plastic sheets covered with odd assortments of broken pots, fragments of plates, and damaged pieces of porcelain have anything to offer to the historian? The Porcelain and Antiques Market (Taoci guwan shichang), otherwise known as the Jingdezhen ‘shard market’, has in fact provided valuable insights for my study of the global history of China and the local impact of that global past.

Fig 1. Entrance to the Porcelain and Antiques Market in Jingdezhen, May 2013. Photograph by the author.

Under the central arch of the shard market’s large entrance gate, with upturned eaves, wooden latticework, and red painted beams, the visitor first encounters this odd collection of items (Fig 1). In the centre stands a striking white bust of Mao Zedong, surrounded by other Maos standing, sitting on chairs, figures made from wood, or from something that looks like jade. Around them are other Communist luminaries, children of the revolution, more Maos, and statuettes of bearded Daoist and Confucian sages, standing side by side with small blue Buddhist lions and a motley selection of pots, vases, cups and plates. This display already hints at the very wide range of materials, colours, periods, tastes and fashions represented by the objects on sale in the market.

It is no coincidence that the vast majority of the antiques for sale are pieces of ceramics. This weekly market takes place in the southern Chinese town of Jingdezhen, which has been known for many centuries as the country’s porcelain capital. The resources found nearby included both the very white porcelain stone (known as bai dunzi or petuntse) and also clay from the Gaoling mountains (known today as kaolin). When blended together and fired at temperatures of over 1300˚C, the molecular structure of these materials changes and they fuse together to form porcelain. Jingdezhen was by no means the only or even the first place where porcelain was produced in China, but the abundance of natural resources and the accumulation of technical knowledge and skill in the area meant that it became the main site of porcelain production for the imperial palace. By the mid-sixteenth century, Jingdezhen was producing ceramics on a massive scale not only to meet imperial demand (as many as hundreds of thousands of pieces were ordered on an annual basis) but also in response to growing demands from overseas. By the eighteenth century, porcelains from Jingdezhen could be found in the royal palaces of Portugal and Spain; the homes of merchants and burghers in England and the Netherlands; in temples in Japan and markets in Mexico City;, on tables in colonial homes in North America; and as architectural features in buildings along the eastern coast of Africa.

Fig 2. Blue-and-white shards for sale in the Jingdezhen shard market, May 2013. Photograph by the author.

As can be seen in fig 2, a huge number of these ‘blue-and-white’ shards (with blue decorations on a white surface) are on sale in the market and this testifies to their mass production and the global demand for this particular decorative scheme. The discerning eye might pick out the birds, flowers, insects, horses, people or dragons’ tails which make up the different patterns, while the uniformity of the blue colour on white surface also makes the shards all look strikingly similar. The Jingdezhen potters were able to produce ceramics on an ever-growing scale yet with only minor adjustments in decorative elements and shapes. And it was this ability of the potters to please consumers all over the globe between the sixteenth and eighteenth centuries which has led many scholars to stress the global aspects of Jingdezhen proto-industrial past.

The traces of Jingdezhen’s global past are certainly visible in the market, too, although the pieces with shapes and/or decorations that betray their intention for overseas markets such as Islamic writing, or Dutch village scenes or British armorial designs have long since disappeared into private circulation. Nonetheless, other traces of Jingdezhen’s global past are still to be found in the market, alongside the local dimensions of this global production, and one question that shaped my research this year in fact concerns the local impact of mass production for domestic and global markets.

Fig 3. Kiln-waster: pieces of porcelain have fused together in the firing process. For sale in the shard market in Jingdezhen, May 2013. Photograph by the author.

Many of the items on sale at the shard market are so-called kiln wasters. The extremely high temperatures inside the kilns meant that not only individual pieces could discolour or collapse, but it was also possible for whole stacks of tightly packed vessels to collapse, or an entire kiln load to fail (Fig 3). As they faced increasing pressure to produce their wares in ever higher quantities and to wider-ranging specifications, the Jingdezhen potters were constantly pushing the boundaries of what was possible technically. For example, in the middle of the sixteenth century, the emperor’s annual demand for porcelains often included so-called “fish bowls”: large vats measuring up to 86 cm high, with a diameter of 94 cm. According to the official records, such vats would cost 55 tael of silver to produce. Considering that the average worker in Jingdezhen was paid no more than seven tael in annual wages around that time, manufacturing such objects represented a substantial investment, and so if the objects failed, this had far-reaching consequences for local finances. Square gin bottles or butter dishes were produced specifically for overseas markets, but if they emerged from the kiln with brown spots or discolouration, they were smashed and buried in pits near the kilns. Through a series of official and unofficial excavations, the materials unearthed from such sites also now come up for sale in the shard market (Fig 4).

Fig 4. Blue-and-white shards, mostly pot bases. For sale in the Jingdezhen shard market, May 2013. Photograph by the author.

The official documentary records of the region as a whole, and of the ceramics industry in particular, are of course immensely valuable for the insights they provide into the production for the imperial court and the management of the industry, which required human and material resources on a vast scale. However, the fragmentary material record of these broken pieces can give us an inkling of something which the official sources are silent about: namely, the local pressures caused by the calls for labour and materials to meet the incessant demand for porcelain from within and beyond the Chinese empire.

The shard market in Jingdezhen, then, can reveal such traces of global connections and local responses, yet the market itself remains to some extent a mystery. How do the goods for sale here find their way to the market, who sells them, and who are the buyers? I have no anthropological training and cannot pretend to be able to answer such questions fully, but I would still like to conclude with some general thoughts on these issues.

Fig 5. Furniture sellers at the Jingdezhen shard and antiques market, May 2013. Photograph by the author.

The market attracts a wide range of traders, including merchants who buy and sell goods found in the surrounding towns and villages. Jiangxi Province is a far cry from the rapid economic growth of the eastern seaboard, and the countryside surrounding Jingdezhen is overwhelmingly poor. Goods like the carved boxes, baskets, earthenware bowls and porcelain statues for sale in Fig 5 are most likely bought cheaply from rural households and sold for a small profit in the market. Traders make the most of the fact that the Jingdezhen shard market is widely known, bringing dealers from far and wide to Jingdezhen on a weekly basis. However, most of the buyers and sellers are there for the porcelain, regardless of the fact that there is no guarantee either that the goods for sale were excavated ethically, or that they are authentic. Undoubtedly, there are all kinds of buyers amongst the crowds arriving at the shard market at the crack of dawn: small-time dealers, priced out of the global art market and especially the global porcelain market, who hope to make a profit from broken but repairable pots; private buyers on the hunt for a piece missing from their collection; students who seek to gain expertise by buying and handling objects otherwise out of reach in museum collections, and, increasingly, foreign tourists and porcelain aficionados. Ultimately, they all share an interest in China’s past. And as for an historian like myself, it is the fragmentary record of both global and local pasts on display in the market that continues to attract me. The shards and fragments for sale in the market serve as a very tangible reminder that we rarely have more than fragmentary remains of the past, even if we aim to construct global stories from them.

About the Author

Anne Gerritsen is Associate Professor of History at the University of Warwick, and from 2013 to 2018, she is affiliated with Leiden University as Kikkoman Professor of Asia-Europe Intercultural Dynamics. Gerritsen was a NIAS Fellow 2013/14, doing research on the Chinese perspective on the global production of porcelain in the early modern period. Photograph by Florence Bernault, 2014